Utmost Good Faith, also known by its Latin term “uberrima fidei,” is a fundamental legal doctrine that legally obliges all parties to an insurance contract to act with complete honesty and transparency, disclosing all material facts that could influence the decision to enter the contract.

A ‘material fact’ is generally defined as information that would influence a reasonable insurer’s decision to accept a risk, determine policy terms, or calculate the premium. The test for materiality is typically objective – would the information have influenced the judgment of a prudent insurer?

Utmost Good Faith goes beyond the standard good faith expected in ordinary commercial contracts. It requires both the insurer and the insured to disclose all material information, even if not specifically asked.

This principle recognizes that insurance contracts are unique because they rely heavily on information that may be known only to one party, typically the insured. Under this doctrine, both parties must refrain from misrepresentation, concealment, or fraud in their dealings.

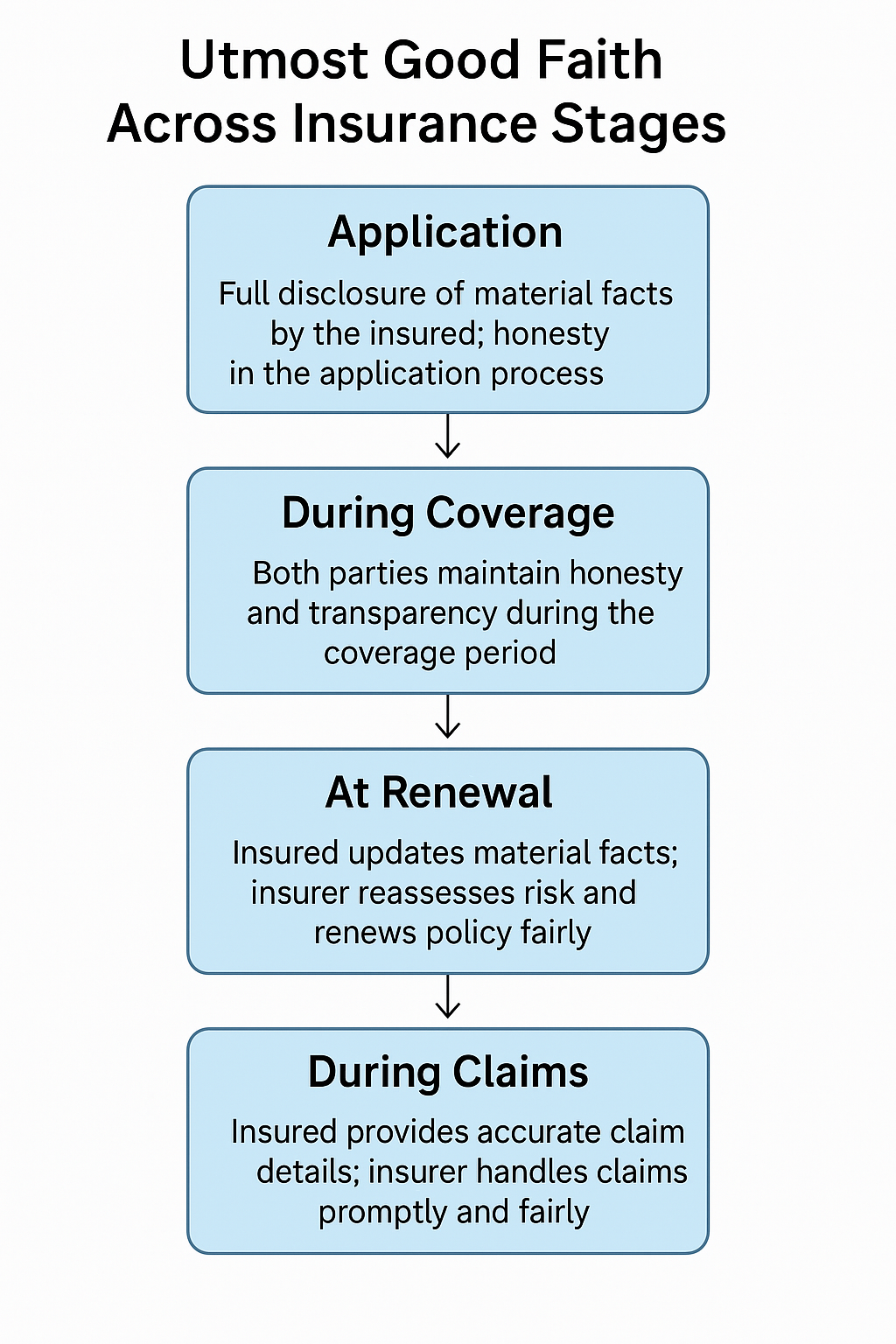

The principle serves as the foundation for the relationship between insurer and insured, ensuring transparency through every stage of the insurance process.

Significance of utmost Good Faith Doctrine in Business Insurance Contexts

In business insurance, Utmost Good Faith plays a crucial role due to the complex nature of commercial risks. Business entities often have unique risk profiles that insurers cannot easily assess without full disclosure from the business owner. This principle ensures that insurers have access to all relevant information to properly evaluate risks and price policies accordingly. For businesses, this means they must be forthcoming about all aspects of their operations that could affect their risk profile, from safety procedures to past claims history. The duty of disclosure extends beyond the initial application to include ongoing changes in business operations.

How Utmost Good Faith Doctrine Functions in Practice

The doctrine of Utmost Good Faith manifests in several ways throughout the insurance relationship. During the application process, businesses must complete insurance applications truthfully and completely.

They must volunteer information that might affect their insurability, even if not specifically asked. For insurers, it means clearly explaining policy terms, exclusions, and limitations.

During claims handling, both parties must continue to act with honesty and transparency. The insurer must assess claims fairly and promptly, while the insured must provide accurate information about the loss. If either party fails to uphold this standard, there can be serious consequences.

Why Utmost Good Faith Matters to Business Owners

If an insured business misrepresents or conceals material facts, the insurer may have grounds to void the insurance policy, leaving the business without coverage when a loss occurs. Even unintentional omissions can potentially lead to claim denials.

The consequences of breaching this duty vary by jurisdiction and policy type. While traditional common law allowed insurers to void policies from inception for any material non-disclosure, many states have adopted more proportionate remedies, particularly for unintentional omissions.

These may include policy reformation, premium adjustment, or partial claim payments rather than complete voidance.

Conversely, this principle also protects businesses by requiring insurers to act honestly in underwriting, policy administration, and claims handling. It provides the foundation for a trustworthy insurance relationship essential for effective business risk management.

Examples of the Utmost Good Faith Doctrine in Practice

Example 1: Manufacturing Company

A manufacturing company applies for comprehensive business insurance coverage. The company has recently installed new machinery that requires specialized training to operate safely, but the operations manager fails to mention this significant change when completing the insurance application.

Six months later, an employee is injured while operating the new machinery without proper training, resulting in a substantial workers’ compensation claim.

When the insurer investigates the claim, they discover the undisclosed new machinery and training requirements.

Under the doctrine of Utmost Good Faith, the insurer argues that this information was material to their risk assessment and would have affected their decision to provide coverage or the premium charged.

The insurer voids the policy from its inception, leaving the manufacturing company without coverage for the workplace injury and potentially exposed to a costly lawsuit.

This example demonstrates how failing to disclose material facts, even unintentionally, can violate the principle of Utmost Good Faith and result in significant financial consequences.

Example 2: Restaurant Business

A restaurant owner applies for property and liability insurance for their establishment. During the application process, the owner truthfully discloses all relevant information, including a small kitchen fire that occurred two years prior, which prompted them to upgrade their fire suppression system.

The owner also mentions their recent implementation of comprehensive staff safety training programs.

The insurance company, operating under the principle of Utmost Good Faith, appreciates the restaurant owner’s transparency and uses this information to properly assess the risk. They acknowledge the upgraded safety measures and training programs as positive risk management steps.

As a result, despite the previous fire incident, the insurer offers the restaurant a policy with a competitive premium that reflects the actual risk based on the comprehensive information provided.

Later, when the restaurant experiences water damage from a burst pipe, the claim process proceeds smoothly because the relationship began with mutual transparency and honesty.

Benefits and Challenges

The principle of Utmost Good Faith promotes transparency between insurers and insureds, creating a level playing field where risk assessment can be conducted accurately.

This leads to fair premium pricing that reflects actual risk exposures. For business owners specifically, this principle ensures that insurers handle claims in good faith and don’t unreasonably deny valid claims.

Additionally, the doctrine encourages businesses to implement better risk management practices, as they must be aware of and able to disclose all aspects of their operations.

However, the doctrine can also presents challenges for businesses. The most significant is the potentially harsh consequence of policy voidance for non-disclosure, even when unintentional.

Small business owners without insurance expertise may not understand what information is considered “material” and thus required to be disclosed.

The standard can sometimes seem subjective, as what constitutes a material fact is not always clear-cut.

Businesses also evolve and change over time, creating an ongoing continuing duty to disclose changes that might affect coverage.

The continuing duty to disclose typically applies to significant changes in risk during the policy period. Business owners should establish procedures to identify and communicate material changes in operations, safety measures, or exposures to their insurers, ideally before these changes are implemented.

This creates an administrative burden that some businesses may find difficult to manage consistently.

Did You Know?

The doctrine of Utmost Good Faith has roots dating back to 1766 when Lord Mansfield established the principle in the landmark English case of Carter v. Boehm.

This historical principle continues to be a cornerstone of insurance law despite its ancient origins.

While this principle originated in marine insurance, where ship owners had exclusive knowledge about their vessels’ conditions that underwriters could not independently verify, it has evolved in American insurance law to apply across all insurance lines.

While this principle originated in marine insurance, where ship owners had exclusive knowledge about their vessels’ conditions that underwriters could not independently verify, it has evolved differently across jurisdictions.

In the United States, application varies by state and insurance type, with commercial and marine insurance generally maintaining stricter standards than consumer lines.

Many states have enacted ‘bad faith’ statutes that modify the traditional doctrine, particularly to protect consumers from harsh consequences for unintentional non-disclosure.

Many other countries have modernized this doctrine through legislation to protect consumers from harsh consequences.

Sources and further reading

The Doctrine of Utmost Good Faith – FindLaw

What Is the Doctrine of Utmost Good Faith in Insurance? – Investopedia

The Argument for Utmost Good Faith in Property Insurance | JD Supra

Understanding Good Faith in Insurance – Restorical Research

The Principle of Utmost Good Faith in Marine Insurance – SSRN

Namic Issue Analysis The Deleterious Effects Bad-faith Litigation Has On Insurance Markets

The 2013 Captive Quandary And The Duty Of Utmost Good Faith

Utmost Good Faith: Follow the Fortunes, The Theory and The Reality